Placenta Previa in Scarred and Nonscarred Uterus and Its Effect on Maternal Fetal Outcome

Abstract

Introduction: Placenta, the life support system of foetus, when implants in lower uterine segment affects fetomaternal outcome adversely. Placenta previa when diagnosed in 2nd or 3rd trimester is associated with series of complications. Placenta previa is a major cause of vaginal bleeding in late 2nd and 3rd trimester.

Objective: To compare feto-maternal outcomes in cases of placenta previa occurring in scarred versus non-scarred uteri.

Methods: This study was prospective observational study, conducted in department of fetomaternal Medicine, BSMMU from January 2023 to June 2024. 60 casesanalyzing of placenta previa managed at a tertiary care center. Patients were categorized into two groups: scarred uterus (n=46) and non-scarred uterus (n=14). Maternal outcomes including hemorrhage, hysterectomy rates, and perioperative complications were compared. Fetal outcomes such as gestational age at delivery, birth weight, and NICU admission rates were also evaluated.

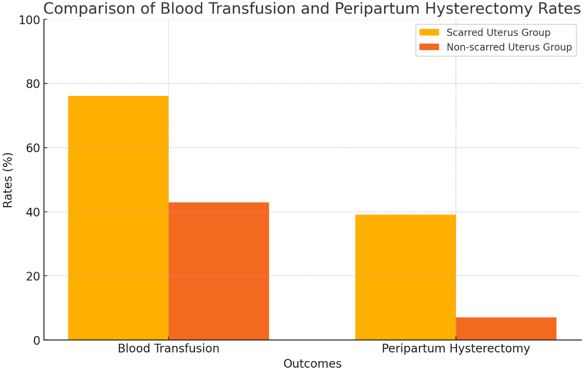

Results: Women with scarred uteri had significantly higher estimated blood loss (1850 ± 950 mL vs 1200 ± 650 mL, p=0.012), increased need for blood transfusion (76.1% vs 42.9%, p=0.021), and higher rates of peripartum hysterectomy (39.1% vs 7.1%, p=0.025) compared to those with non-scarred uteri. Placenta accreta spectrum disorders were more common in the scarred uterus group (37.0% vs 7.1%, p=0.038). After adjusting for confounding factors, having a scarred uterus remained an independent risk factor for peripartum hysterectomy (aOR 6.2, 95% CI 1.8-21.5, p=0.004) and for requiring blood transfusion (aOR 3.8, 95% CI 1.2-12.1, p=0.023). Fetal outcomes showed a trend towards being poorer in the scarred uterus group, but these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusion: Placenta previa in the context of a scarred uterus is associated with significantly worse maternal outcomes, particularly in terms of hemorrhage, transfusion requirements, and hysterectomy rates. These findings highlight the importance of strategies to reduce primary cesarean section rates and emphasize the need for specialized care in managing pregnancies complicated by placenta previa in women with previous cesarean deliveries.

Downloads

References

2. Getahun D, Oyelese Y, Salihu HM, Ananth CV. Previous cesarean delivery and risks of placenta previa and placental abruption. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(4):771-778.

3. Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. The association of placenta previa with history of cesarean delivery and abortion: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(5):1071-1078.

4. Boerma T, Ronsmans C, Melesse DY, et al. Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean sections. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1341-1348.

5. Jauniaux E, Jurkovic D. Placenta accreta: pathogenesis of a 20th century iatrogenic uterine disease. Placenta. 2012;33(4):244-251.

6. Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries: early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(1):14-29.

7. Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):331-337.

8. Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):561-568.

9. Crane JM, Van den Hof MC, Dodds L, Armson BA, Liston R. Neonatal outcomes with placenta previa. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(4):541-544.

10. Balayla J, Wo BL, Bédard MJ. A late-preterm, early-term stratified analysis of neonatal outcomes by gestational age in placenta previa: defining the optimal timing for delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(15):1756-1761.

11. World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194.

12. Jauniaux E, Alfirevic Z, Bhide AG, et al. Placenta Praevia and Placenta Accreta: Diagnosis and Management: Green-top Guideline No. 27a. BJOG. 2019;126(1):e1-e48.

13. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). 10th revision, 2016 edition. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

14. Worster A, Haines T. Advanced statistics: understanding medical record review (MRR) studies. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(2):187-192.

15. Collins SL, Ashcroft A, Braun T, et al. Proposal for standardized ultrasound descriptors of abnormally invasive placenta (AIP). Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(3):271-275.

16. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 7: Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(6):e259-e275.

17. Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Logistic Regression: A Self-Learning Text. 3rd ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

18. Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady D, Newman TB. Designing clinical research: an epidemiologic approach. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

19. Grobman WA, Gersnoviez R, Landon MB, et al. Pregnancy outcomes for women with placenta previa in relation to the number of prior cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(6):1249-1255.

20. Usta IM, Hobeika EM, Musa AA, Gabriel GE, Nassar AH. Placenta previa-accreta: risk factors and complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 Pt 2):1045-1049.

21. Jauniaux E, Chantraine F, Silver RM, Langhoff-Roos J; FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Epidemiology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140(3):265-273.

22. Cheng KK, Lee MM. Rising incidence of morbidly adherent placenta and its association with previous caesarean section: a 15-year analysis in a tertiary hospital in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21(6):511-517.

23. Frederiksen MC, Glassenberg R, Stika CS. Placenta previa: a 22-year analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(6 Pt 1):1432-1437.

24. Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1226-1232.

25. Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries: early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(1):14-29.

26. Balayla J, Wo BL, Bédard MJ. A late-preterm, early-term stratified analysis of neonatal outcomes by gestational age in placenta previa: defining the optimal timing for delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(15):1756-1761.

27. Pivano A, Alessandrini M, Desbriere R, et al. A score to predict the risk of emergency caesarean delivery in women with antepartum bleeding and placenta praevia. Eur J ObstetGynecolReprod Biol. 2015;195:173-176.

28. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 205: Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(2):e110-e127.

29. Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):561-568.

30. Jauniaux E, Bhide A. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis and outcome of placenta previa accreta after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(1):27-36.

Copyright (c) 2024 Author (s). Published by Siddharth Health Research and Social Welfare Society

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

OAI - Open Archives Initiative

OAI - Open Archives Initiative

Therapoid

Therapoid