Study of 24 weeks antenatal visit as predictor of perinatal outcome

Abstract

Introduction:Once the pregnancy progresses to 24weeks, almost all the congenital anomalies and teratogenicity are ruled out. The progress there after is influenced by the maternal and obstetric factors. There is a need to establish the significance of all these variables with perinatal outcome and for thorough analysis. This study was focused on all low risk patients at 24 weeks of gestations to determine maternal factors affecting the perinatal outcome.

Methods: The present study was a prospective observational study of 50 cases conducted in the Outpatient department of Obstetrics &Gynecology of Padmashri Dr. D. Y Patil, Hospital and research institute, Kadamwadi, Kolhapur. The patients were advised all the regular investigations and thedata collected was analyzed to determine maternal or fetal factors affecting the perinatal outcome.

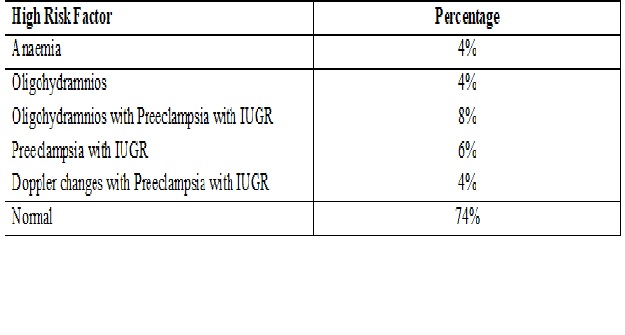

Results: 82% had normal Blood pressure and 18% patients had signs of pre-eclampsia. Factors leading to high risk pregnancy were 8% with oligohydramnios with preeclampsia with IUGR, 6% preeclampsia with IUGR, 4% each anemia; Doppler changes with preeclampsia with IUGR, oligohydramniosrespectively.

Conclusion:In this study, late onset preeclampsia and anemia are the factors that are not detected at 24 weeks. It is also observed preeclampsia and anemia leads to IUGR. All the complications occurred after 36 weeks of gestational age, that means patient needs definite and regular follow up after 36 weeks.

Downloads

References

2. Registrar General Annual Report 2014. Still birth and Infant death. Available at: http://www.nisra.gov.uk/archive/demography/publications/annual_reports/2014/Stillbirths.pdf. Accessed on July 2, 2015.

3. Smith GC, Fretts RC. Stillbirth. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61723-1.[pubmed]

4. Stillbirth in developing countries: a review of causes, risk factors and prevention strategies. J MaternFetal Neonatal Med. 2009 Mar;22(3):183-90. doi: 10.1080/14767050802559129.[pubmed]

5. Clausen C, Lönn L, Langhoff-Roos J. Management of placenta percreta: a review of published cases. Acta ObstetGynecol Scand. 2014 Feb;93(2):138-43. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12295. Epub 2013 Nov 25.[pubmed]

6. Vilar J, Say L, Gulmezoglu M. Eclampsia and preeclampsia: A worldwide health problem for 2000 years. In: Critchley H, Mac Lean A, Poston L, Walker J (Eds). Preeclampsia. London: RCOG Press; 2007.p.189-207.

7. Sibai BM, Spinnato JA, Watson DL, et al. Pregnancy outcome in 303 cases with severe preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 1984 Sep;64(3):319-25.[pubmed]

8. Manktelow BM, Smith LK, Evans TA, Hyman-Taylor P, Kurinczuk JJ, Field DJ. MBRRACE-UK Perinatal Mortality Surveillance Report UK Perinatal Death for Births from January to December 2013 – Supplementary Report: UKTrusts and Health Boards. Leicester: The Infant Mortality and Morbidity Studies Group, Department ofHealth Sciences, University of Leicester, 2015.

9. Roberge S, Nicolaides KH, Demers S, et al. Prevention of perinatal death and adverse perinatal outcome using low-dose aspirin: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013 May;41(5):491-9. doi: 10.1002/uog.12421.[pubmed]

10. Byun YJ, Kim HS, Yang JI, et al. Umbilical artery Doppler study as a predictive marker of perinatal outcome in preterm small for gestational age infants. Yonsei Med J. 2009 Feb 28;50(1):39-44. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2009.50.1.39. Epub 2009 Feb 24.

11. Bramham K, Briley AL, Seed P, et al. Adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes in women with previous preeclampsia: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;204(6):512.e1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.014. Epub 2011 Mar 31.[pubmed]

12. Thabane P. Impact of Severe Preeclampsia on Maternal and Fetal Outcomes in Preterm Deliveries. [dissertation]. Johannesberg [University of Witwatersrand], 2013, 1-106.

13. Aabidha PM, Cherian AG, Paul E1, et al. Maternal and fetal outcome in pre-eclampsia in a secondary care hospital in South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015 Apr-Jun;4(2):257-60. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.154669.[pubmed]

14. Kenneth L, Hall DR, Gebhardt S, et al. Late onset preeclampsia is not an innocuous condition. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2010;29(3):262-70. doi: 10.3109/10641950902777697.[pubmed]

15. Sultana, Aparna J. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia and its perinatal outcome. Scholars Research Library Annals of Biological Research. 2013;4(10):1-5.

16. Seyom E, Abera M, Tesfaye M, Fentahun N. Maternal and fetal outcome of pregnancy related hypertension in Mettu Karl Referral Hospital, Ethiopia. J Ovarian Res. 2015; 8:10, doi.10.1186/s13048-015-0135-5

17. Gasparovic VE, Beljan P, Ahmetasevic SG, Schuster S, SkrablinS.What affects the outcome of Severe preeclampsia. Signa Vitae.2015;10(1):6-12.

18. Turning the Pyramid of Prenatal Care Kypros H. Nicolaides a, b a Harris Birthright Research Centre of Fetal Medicine, King’s College Hospital, and b Department of Fetal Medicine, University College Hospital, London , UK

Copyright (c) 2019 Author (s). Published by Siddharth Health Research and Social Welfare Society

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

OAI - Open Archives Initiative

OAI - Open Archives Initiative

Therapoid

Therapoid